White-tailed and mule deer tracks are nearly identical and there are no proven methods for accurately differentiating these species from single tracks. Habitat and behavior are better clues to species. Mule deer are known to use a bouncing gait known as a “pronk” or “stot” that white-tailed deer do not use.

Click here to read my article on how to tell buck from doe tracks.

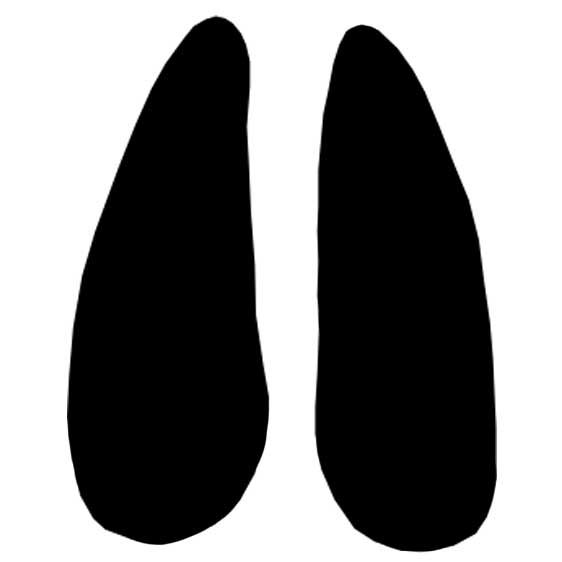

Deer Front Track

- 1.8 – 3.2 in (4.6 – 8.1 cm) long.

- 1.5 – 2.6 in (3.8 – 6.6 cm) wide.

- 2 hoofed toes (cleaves) form a heart-shaped track. Toes are pointed. The outer wall is slightly convex or straight. The inner wall is usually straight or slightly concave.

- Two dewclaws may register in soft substrate or when moving fast. Front dewclaws are slightly closer to the hoof and angled outward more than those of the hind track.

- The track is symmetrical.

- Slightly larger than the hind track.

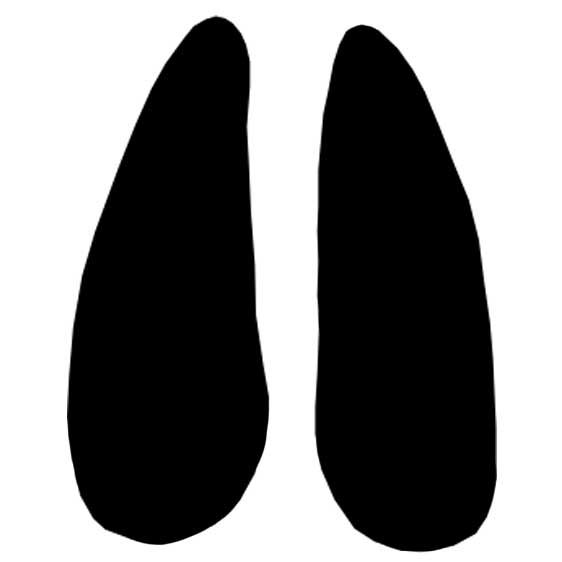

Deer Hind Track

- 1.5 – 3 in (3.8 – 7.5 cm) long.

- 1.1 – 2.6 in (2.8 – 6.6 cm) wide.

- 2 hoofed toes (cleaves) form a heart-shaped track. Toes are pointed. The outer wall is slightly convex or straight. The inner wall is usually straight or slightly concave.

- Two dewclaws may register in soft substrate or when moving fast.

- The track is symmetrical.

- Slightly smaller than the front track.

Photos of White-tailed Deer Tracks

White-tailed deer tracks usually show 2 toes (cleaves) that form a heart-shaped track. The front track (on right) is larger than the hind (on left).

Two splayed white-tailed deer tracks. Tracks often splay in mud or when the animal is traveling fast. The front track is on the right.

In this hind track all 4 toes are showing. Toes 3 and 4 make up the hoof and toes 2 and 5 register as dewclaws behind the hoof. The dewclaws in front tracks are closer to the hoof and point more to the outside.

Photos of Mule Deer Tracks

Front and hind tracks show 2 toes reliably that form a characteristic upside down heart-shape. I do not know a way to differentiate mule deer from white-tailed deer from a single track.

Hind tracks are slightly smaller than fronts. The hind track is partially on top of the front in this image.

All 4 toes are showing in this front track. Toes 3 and 4 make up the hoof and toes 2 and 5 register as dewclaws behind the hoof. Note that the dewclaws are slightly wider and closer to the hoof than in the hind track.

In this hind track all 4 toes are showing. Toes 3 and 4 make up the hoof and toes 2 and 5 register as dewclaws behind the hoof.

White-tailed and mule deer scat are very similar and I do not know of any proven methods for telling them apart in the field.

White-tailed Deer Scat (Feces)

White-tailed deer scat comes in a variety of forms. Usually it consists of numerous oblong pellets with a small dimple on one end and a small point on the other. Photo by George Leoniak.

Mule Deer Scat (Feces)

Both mule and white-tailed deer scats may clump together when there is sufficient moisture in the diet.

White-tailed Deer Sign

Bucks rub small saplings with their antlers during late summer and fall. This serves to remove velvet and as a territorial marker.

Mule Deer Sign

Mule deer bucks will rub their antlers on trees and branches as part of a territorial marking behavior during breeding season.

A mule deer bed in tall grass. Their beds often have a roughly triangular shape, narrower toward the head and broader toward the rump. White-tailed deer leave similar beds.

The following images are the recent white-tailed and mule deer track and sign observations from the North American Animal Tracks Database. This is an iNaturalist project where trackers share observations and help each other learn about animal tracks, all while contributing to scientific research. Identifications of tracks on this page are initially made by members of the public and may not be correct. The tracks will eventually be verified by experts.

There are many great guides to identifying animal tracks. While a few are truly excellent, there are others with surprising inaccuracies. The guides below are my absolute favorites and won’t lead you astray. If you decide to purchase any of these guides, using the links below will help support future developments to this website.

iTrack Wildlife is my own guide to animal tracks for the iPhone and Android. It has over 700 high resolution photos of tracks, scats, sign, and skulls. It also has over 120 accurate track drawings for 66 mammals. What makes this app really different from other guides to animal tracks is the search tools that let you quickly narrow down a track by size, the number of toes, the shape of the toes, track symmetry, the mammal group, and the state or province.

Mammal Tracks and Sign of North America by Mark Elbroch is the modern bible of animal track and sign identification. Its publication drastically changed the field of animal tracking and spawned a renewal of interest in the field. It has hundreds of color photos and precise track drawings. The book is organized by the type of sign (tracks, scats, chews, digs, etc) making it easy to identify sign, but not great if you want to read about all the details of a single species. Also, the comprehensive nature of this book makes it an amazing resource, but it can be quite a load in your backpack. If you don’t own this book and you’re serious about tracking, you should definitely get it.

Animal Tracks and Scat of California is a regional guide, but many of the species are found throughout North America. This guide includes mammals, birds, and even some reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates. It is a great general tracking guide (full disclaimer: I am a co-author of this guide) and is a great bet if you want a single guide that covers more than just mammals. This book also has some helpful sections not found in Bird Tracks and Sign including a quick reference to life-sized bird tracks.

Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest is a regional guide written by my friend and excellent tracker David Moskowitz. While the book primarily focuses on the Northwest, much of the information applies nationwide. This tracking guide includes mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates. The guide also contains excellent original artwork and beautiful photography. This guide is truly worth adding to your library.

The Peterson Guide to Animal Tracks is the classic tracking guide. This book was published in 1954 and inspired many trackers and naturalists. It was a major work for an author at the time with so few other resources available and predictably it contained several small errors. In 2005 is was updated by Mark Elbroch who made corrections, added information, and many photos.

Tracking and the Art of Seeing by Paul Rezendes was the first animal tracks guide in North America to contain color photographs. This guide drastically changed the landscape of future tracking guides. For example, just about every single subsequent field guide uses a similar stipple-point style for drawing tracks. This guide is more of a desk reference and is great reading. It is organized by species, so it is great for learning about an animal, but difficult to use to identify a particular type of sign.

A Field Guide to Mammal Tracking in North America by Jim Halfpenny is a classic guide that led to many advances in animal tracking. While the guide doesn’t contain color photos of tracks, there is a valuable scientific approach to identifying tracks that has very practical applications. He also covered gaits and animal movements in the most comprehensive manner at the time. While there are newer guides with perhaps more accurate information available, this guide made them possible.

The Animal Tracks: Midwest Edition by Jonathan Poppele is a book that surprised me. I expected this guide to be just another low quality pocket guide. However, what I found was anything but low quality. It has fantastic track drawings, accurate information, and a very handy organization method. This book is inexpensive and worth adding to your library.

Looking for More?

Sign Up to Get News, Updates, and Tracking Tips by Email.